Last Monday, I participated in the podcast “Market Lab,” hosted by Dirceu Simões of APEX partners. APEX is a regional force in the Brazilian real estate, wealth management, and investment banking markets, with over $2 billion under management.

For this week’s post, I have translated the Portuguese transcript into English and selected some highlights, which are printed below.

The conversation was divided into three parts: a discussion about my early connection to Brazil and how my career brought me from Wall Street to São Paulo; a conversation about the “regime change” we are experiencing in the global markets; and finally, a discussion about the dynamics in the Brazilian local markets.

Because this post runs longer than usual, I have labelled each of these three sections, so you can pick and choose which, if any, of these topics interests you.

You can also listen to the whole podcast here, in Portuguese:

Part I - Wall Street Beginnings

Dirceu (host):

Hello everyone, welcome to another episode of Market Lab, one of the communication initiatives of the BRM Podcasts family, produced by APEX Partners and Mendonça e Machado.

Today, we’re welcoming our guest, David Wolf, with extensive market experience, to talk about a topic that’s been taking up a lot of time for both local and international managers, which is precisely a regime change from the last decade, basically the American exceptionalism, a very strong American outperformance, and perhaps there are signs that things might be different moving forward.

But before diving into the topic itself, David, it’s good for us to understand who you are, what your career path in the market has been, and what lessons from your journey contribute to today’s analysis.

David:

Well, thank you for the invitation, thank you to APEX. It’ll be interesting to talk to your audience. I’ll try to be brief and concise. You’ve probably noticed I have an accent. I’m from the United States. I arrived in Brazil in 1995, married a woman from São Paulo, and built my life here.

But going back to the beginning, there are even some connections with Brazil from way back. I’m from Washington. DC. My father worked at the IDB, the Inter-American Development Bank, at the time, and as a result, he had to travel a lot to Latin America, including Brazil. He took the family along, and I became passionate about Brazil for many reasons.

One of them, quite interesting—you remember Pelé played in the United States? I had the luck of watching Pelé when he played for the Cosmos. So that was one thing. And then the second interesting thing: I started a business as a teenager, an entrepreneurial venture. My company was called Brazilian Imports, and I brought jewelry, pendants, necklaces, and decorative objects made with Brazilian semi-precious stones—amethyst, agate, and tourmaline. I had a team of five people from my high school, and we sold these items as street vendors in downtown Washington. It was something we did in the summer, and with the sales, I visited Brazil to buy the merchandise, so I had a connection with Brazil.

To continue, after college, I went to New York. Life and the markets were very different back then. I had studied philosophy, and with a philosophy degree, you can do nothing or anything. At that time, you didn’t need the specialization that people need today—it’s much harder now. I knocked on some doors and, I think I’d say by luck, landed a junior-of-juniors role, basically an entry-level position at a trading desk, in a very important area that grew a lot: mortgage-backed securities. I’m talking about 1986.

That was a market that boomed at the time, and the bank was PaineWebber, which was eventually bought by UBS. I stayed in New York for four years and became a market maker for mortgages.

Then the bank sent me to Tokyo, where I stayed for four years. Tokyo was very interesting because, from 1989 to 1993, that’s when CNN started, so for the first time, we had live televised news impacting the market. There was the first Gulf War, and you had those scenes of bombs falling, the market moving, and oil prices swinging back and forth.

Then I went to London, doing the same thing—market-making for clients in that region. From there, I transitioned to emerging markets and got an invitation to join Cargill. Cargill is the largest private company in the United States, a family-owned business. For those who don’t know, it’s a multinational that does a lot of things, but its strength is agricultural trading. Here in Brazil, they’re either the number one or number two exporter of soybeans and soybean derivatives.

As a very large and diverse company, Cargill had an area that was almost like an internal hedge fund because, operating in local markets—whether in Buenos Aires, São Paulo, or Singapore—they had expertise in legislation and policy. They were smart and opened offices with teams to operate in local markets. I joined that desk here in Brazil, starting in fixed income, and eventually, we did a lot of things.

Let me give you a super interesting example. At the time, we had literally hundreds of millions of dollars in the country because interest rates were very high, and you could hedge the local currency to the dollar and get fat returns. We could bring money into the country easily. We’ll talk about IOF (financial transaction tax) later, but back then, an IOF was charged on entry, which is interesting—you paid to access the local market.

I won’t go into details, but exporters like Cargill had a legal way to finance local market investments and bring money in without having to pay the entry tax. We created structured notes to give Wall Street—the biggest banks on Wall Street—access to the local market here. It was a multinational that ended up selling Brazilian bonds wholesale to our clients, who were the big banks like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and so on. The investment banks would then sell those participations on to their clients. It gave me experience in structuring.

During the ten years I spent at Cargill, we also opened a bank. Cargill Bank still exists today—it’s the only bank the company has in the world. It was a two-year project. You know how the financial market here is very professional—everything, all the systems, has to be very rigorous. The financial market here is quite secure. We saw how in the 2007 banking crisis how Brazil suffered very, very little. So, that wraps up my 10 years at Cargill.

Finally, just to touch on, after Cargill I went to Unibanco (a large Brazilian bank) as treasury director, then spent two years at a hedge fund in London that became part of BTG, called Lentikia.

Then I left the market and entered the real economy. I had a food truck company, the number one food truck company in Brazil, but we didn’t make food—we rented out our huge, fully branded, beautiful trucks to big clients like Nestlé, Vigor, and Outback. That worked well, although being a foreigner doing business in Brazil’s real economy is a challenge. The clients would take our trucks on tours and events to promote their products. Then COVID hit, and obviously, things came to a halt.

I returned to trading institutionally as a Portfolio Manager at Armor Capital, here in São Paulo in 2023.

Part 2: Regime Change - The interregnum in the US market

Dirceu:

David, let’s move on to the episode’s topic now. Before we talk about the topic, you write a weekly letter, right? On Monday mornings, you send it to everyone. That’s where the inspiration to invite you came from, to talk exactly about this.

Since Liberation Day, April 2nd, we’ve entered a theme of a stronger dollar, or rather, a weaker dollar, sorry, a reversal of the strong dollar we’ve seen in the last decade, but especially post-COVID. This is largely due to a perception of greater risk in the United States and also a very different price level between what’s being practiced in the U.S., both in terms of currency and the stock market, compared to the rest of the world.

You’ve been addressing in your newsletter, and it’s something the market has been talking about for a while, a possible regime change. The old regime we lived under until Trump’s election was one of American exceptionalism. American exceptionalism isn’t just about these 10 years—it’s a term that goes way back, but the financial market specifically experienced it strongly, especially from 2015.

The U.S. stock market outperformed, and the US had the most dynamic economy and the best companies in the world. It was truly something sensational that happened there. The dollar, too, as a currency, had a very strong performance, not just against the (Brazilian) real, but against all the world’s currencies.

And we started to see a reversal of that narrative at the beginning of the year. So, how do you define this regime change? What are the main factors driving this shift?

David:

I think the most important word here is “change” because there’s this thing called an “interregnum,” right? So, we try not to make predictions about what the world will be like in two or three years. We don’t know what regime is coming. We are between regimes.

Especially today, it’s impossible to know structural outcomes, even not even their probabilities, in the long term. As portfolio managers, as investors, we look at a slightly shorter term horizon— the next six months—because things are very, very dynamic. We are in an interregnum.

Up to Liberation Day, an international investor investing in the United States had three advantages. First, you had the tech sector, as you mentioned. If you bought an S&P ETF, you made a lot of money because of the big tech companies that dominate the index. Second, you had the advantage of the exchange rate. The dollar got stronger every time there was a crisis, so you were protected. And third, you had an inverse relationship between bonds and stocks.

And to talk a bit about the regime change, where we are—well, we’re in between a “reign” that’s over, defined by globalism, an America close to NATO, American institutions which worked in a given way for a long time. Whether it’s the geopolitical alliances, the justice system, the universities, or the regulatory framework, there are big changes that Trump is making, or trying to make.

He’s shaking things up tremendously, but there is institutional inertia that works against change. Even though he’s a President with a lot of power, elected with the entire Congress, you have to remember that almost fifty percent of Americans are strongly against Trump. So, there’s resistance to his increasing executive powers. The tariffs are a good example.

We’ve seen in recent days some courts saying tariffs by executive order are illegal and others saying they are legal. This will be resolved by the Supreme Court, where Trump has a majority of conservative justices, but we don’t know how they’ll handle these cases, which will be very important.

So, you have this soup—you know the ingredients that went into it, but you don’t know what the flavor will be. It’s still simmering.

Diversification becomes very important. I don’t want to sound cliché—diversification is a cliché - but clichés are clichés because they have a lot of value behind them. Now, what kind of diversification do you want?

I think it’s important to look at your portfolio and have assets or strategies that will work under various outcomes.

What happens to my portfolio in an inflationary environment? What do I need in my portfolio to protect against inflation?

It is also important to consider an alternative scenario: If we have a recession in the U.S., or even globally, what assets will help me? Or another: if tech continues to benefit from this AI miracle, we know there might be a negative effect on employment initially, but maybe a positive one later. We know it can drive a big rally.

So, it’s hard to know what will happen with this soup, what it will taste like. We have to protect ourselves and be prepared for various scenarios like the three I mentioned.

A portfolio that is 100% in the U.S., 100% “dollarized,” I don’t think will deliver the returns of something more diversified, with commodities, with other currencies, and with careful selection of equity sectors.

Dirceu:

The flow of investment to the U.S. was huge, also due to the negative U.S. trade balance for treasuries. Governments were big buyers of treasuries. But after 2017, especially post-COVID, the same huge flows went to the US stock market.

With this combination of high valuations and concerns about the trajectory of U.S. debt, which ties into Trump’s economic program, we started to see a reversal of that flow. I have two questions.

First, is the policy idealized by Trump capable of reversing this fiscal trajectory that even Janet Yellen admitted is unsustainable?

And second, which you already touched on, the checks and balances in the U.S., the huge inertia—can significant changes be made? Will the executed policy be very different from what’s being designed?

Recently, we had the approval in the House of the Reconciliation Bill, which would be equivalent to our fiscal framework here in Brazil. It didn’t turn out as good as promised, even below market expectations.

So, the question is, okay, the old regime is gone, we don’t know what’s coming next. Will the combination of what the U.S. government is doing now be able to stop this outflow from the U.S., this diversification to other assets?

David:

I don’t think so. I think this period is over. If we think about the period as a “reign,” the queen is dead. We don’t know who’s coming next. We’re in between these periods. Even if Trump reverses course, we can’t go back.

Obviously, with the speed things are happening, he has the power to change directions. That happens with every tweet he makes. As you mentioned, checks and balances well mean some reversals, with Trump getting some wins but also taking some losses.

Regarding the budget you mentioned, “reconciliation” means Congress takes a budget outline and has to reconcile it with the law. Congress must design legislation that aligns with the guidelines of the party in power. What Trump would like to see in terms of government spending, revenue, taxes, and how the government spends money—it’s true, what came out of the House does not give us much optimism about the U.S. deficit.

The calculations are super hard because you don’t know what the inflation rate will be, you don’t know how much GDP will grow, what revenue tariffs will bring in, and you don’t know the elasticity of some tax rates on economic activity. You have to make a lot of assumptions.

From what I have studied, for the U.S. fiscal deficit to reach 3% in 2028, which is Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s stated policy objective, US GDP would need to grow nominally—meaning inflation plus real growth—at 9% per year, without cutting spending.

Now it goes to the Senate, but I don’t know what the Senate will do. Unfortunately, for the economy, it won’t bring the deficit down. So, when Mr. Bessent talks about reaching a 3% deficit with 3% growth—the famous 3-3-3 plan—I don’t see how. I don’t see how, unless there’s massive inflation, which would create a recession, which would make tax revenues fall and the budget deficit increase even more.

The US has become a little bit like Brazil. Before, when the 10-year yield rose, the US dollar appreciated against other currencies. In emerging markets like Brazil, you would see exactly the opposite - when there’s stress in the market, interest rates go up, and the currency goes down. But now the US is trading like Brazil. When there is stress, the dollar goes down even as interest rates go up. The loss of the inverse has scared everyone.

Part 3: The Brazilian Markets - It’s the real, stupid

Dirceu:

David, the world is pulling out of the U.S. and moving to other geographies. I’m not saying Brazil is the beneficiary of this, but we saw inflows, even if they are passive, where new money has come into emerging markets ETFs, and it ended up here. Or they deliberately invested in Brazil specifically.

We saw, at the start of the year, after a lot of market stress after the first quarter, a very depressed price level, which contributed to the recovery. But we saw a significant foreign inflow into Brazil, benefiting from this global reallocation due to a weaker dollar.

But we haven’t seen an improvement in Brazil’s fundamentals specifically. We still have the same problems we had at the end of last year, and now, more recently, the Brazilian news cycle has started to get negative again after a calm period of three or four months.

You, with experience abroad, being American, having worked in the U.S. market and the Brazilian market, do you see a big difference in how the foreign investor treats this new cycle? Does it closely influence their decision-making, or not?

David:

In this specific case, let’s take the government’s surprise announcement a couple of weeks ago of a new IOF, a tax on remittances - a package of bad measures—higher taxes, the worst kind of taxes, restricting credit, restricting free flow. It’s exactly what you said—it became so easy to invest anywhere in the world, and then Brazil goes and does something super heterodox, going back to when I arrived here.

But I think the foreign investor didn’t care because the market reaction forced the Finance Ministry to reverse most of the bad measures in the package. Overnight! That part was super important. That ability to react—I wish the U.S. would do that. When they make a mistake, it’s hard for them to backtrack so quickly. Brazil was very reactive.

I think for us locals here in Brazil, we get frustrated with the government’s incompetence, but for the foreign investor, they’re like, “Look, the government reversed course, so it’s fine. I’ll stick with my diversified plan, moving away from the dollar.”

The fact is, Brazil has the highest carry-to-volatility ratio in the world, by far—Mexico is second but way behind. This real interest rate we have in Brazil is hard to ignore. (Real interest rates in Brazil are above 7%).

It’s hard not to receive some inflows when you have this regime change happening. Some money will bubble up here in Brazil. I agree with you—nothing has changed in terms of Brazilian fiscal problems or election risks. My opinion is that both the foreign and overall markets are underestimating the possibility of (current leftist president) Lula, winning reelection in 2026.

The foreign investor is aware of this, but I think they see so much positive upside if if Lula loses and a candidates from the conservative right wins. If it’s a 60% chance of the right winning, they’ll take the risk that Lula wins. In other words, they are willing to pay to play.

Dirceu:

That’s clearer now, well answered. You gave your opinion on the local investor—I think they’re a bit sensitive, and I agree with you. They’re very optimistic about the possibility of a change in power. It’s still very early, more than a year and a half, 1 year and 4 months until the election. We don’t even know if it’ll be Tarcísio (the market’s favorite right-wing candidate). I agree with you that it’s too early.

One thing is, Lula has already started reacting again to his loss of popularity. He’ll keep trying to reverse this picture. This was the first of the measures that came up. We don’t know what’s coming next. I’m sure more will come, and we’ll see how much people can handle.

You mentioned rates moved. We have two rates, right? We have the real rate and the nominal rate. The nominal rate moved a lot. The real rate dropped 50 basis points, but the drop was much greater in the nominal rate. Do you see a difference in pricing between the two?

It’s a medium- to long-term play, right? In the short term, a pleasant surprise was (Central Bank President Gabriel) Galípolo’s positioning. There was a lot of doubt about how he’d behave, but so far, he’s calmed the market quite a bit.

As you well reinforced, it doesn’t seem like he’ll move. He might stop raising rates, but it doesn’t seem like he’ll move to cut anytime soon. So, those who want to wait and see the interregnum a bit more can sit comfortably in CDI, right?

David, we’re running out of time here. I’d like to thank you so much for your presence. And I’d like to know if you have any final comments or recommendations.

David:

Yes, yes. For me, the value is clearly in the real rates in Brazil - inflation-linked bonds. But speaking of technical positioning, the technicals in that market are not good because the Treasury keeps selling, selling, selling. I don’t know if it’s true, but the market’s reading is that foreigners don’t buy NTN-Bs. I don’t know if they buy or not now.

Having worked as an international investor, I don’t see why they wouldn’t buy them, but we can’t know in real-time.

So, I think for the patient local investor, the inflation bonds are very interesting. If there’s a really big crisis, and inflation spikes, that could be a cause of new demand, and the rates on the bonds might even fall, so they have an interesting convexity.

I think it’s a good bet that Real could keep getting stronger. I think it has strength based on this carry. The positioning isn’t bad.

The stock market, on the other hand, I think, is very stretched. I think some local players arrived late. Because it’s been rising, and there’s a lot of pressure to chase the market.

Rates have moved a lot, too. Inflation is far from certain to converge to the Central Bank’s target. The yield curve is already pricing in rate cuts this year, and that is very, very optimistic. Possible, but very optimistic.

The rate-cutting cycle could indeed reach 300 basis points. So, the moment the market thinks we’re entering a rate-cutting cycle, it could validate today’s market prices. But, as you say, there’s a lot of time until the election, a lot of time until rates are cut.

They won’t cut today, not in the next three months, maybe not in six months, maybe at the end of the year. The Central Bank would lose total credibility because if they’re saying inflation expectations are unanchored, i they are not going to become anchored in two or three months—I don’t know how.

Thank you, Dirceu, for the invitation and the opportunity to be here today. It was a pleasure to talk with you and your audience. I think the key takeaway, whether we’re talking about Brazil or the international market, is to stay alert. The markets are moving fast, and things are changing in ways we haven’t seen before.

For investors, my recommendation is simple: don’t put all your eggs in one basket. We’ve talked about diversification, and it’s critical now more than ever. Whether it’s Brazil’s high real rates or opportunities in other emerging markets, there’s value out there, but you have to be selective and understand the risks.

I think the times we’re living in now are more fascinating than anything I’ve ever seen. For young traders, they have already seen the Covid crisis, and now they are seeing this regime change. That experience is priceless.

I went through several crises, and obviously, you get stronger after suffering—you come out stronger. But what we’re seeing today with Trumpomics, the way he’s dealing with other countries, and how other countries are responding to him—not just economically but geopolitically, legally, domestically—it’s a fascinating moment.

So, for me, despite all these experiences, I learn something new every day. It’s not a lie—it’s another cliché that’s true. And finally, I’d like to invite everyone to read my Macro Monitor, which I call the wolf of wall street.

Dirceu:

It is cool. Thanks a lot. I recommend a light read, 20 minutes on Monday morning over coffee—it’s enough to get up to speed.

Fantastic, David, thanks so much for the insights and for sharing your journey with us. It’s been a fascinating conversation, from your early days with Brazilian Imports to navigating global markets and now analyzing this regime change.

One cool point you brought up is that those entering the market now are living through a turbulent period. Here in Brazil, we always have crises, but abroad, there was COVID, and now there’s this Trumpomics episode. The previous generation, the one that entered the market after the subprime crisis, had a smooth ride, one of the calmest in history. You experienced slightly more turbulent times, but this is a very different generation with a very different formation compared to the one before.

It’ll be exciting to see how the market develops from this. David, thank you so much for being here.

David:

Thank you, Dirceu, it was great.

Macro Monitor

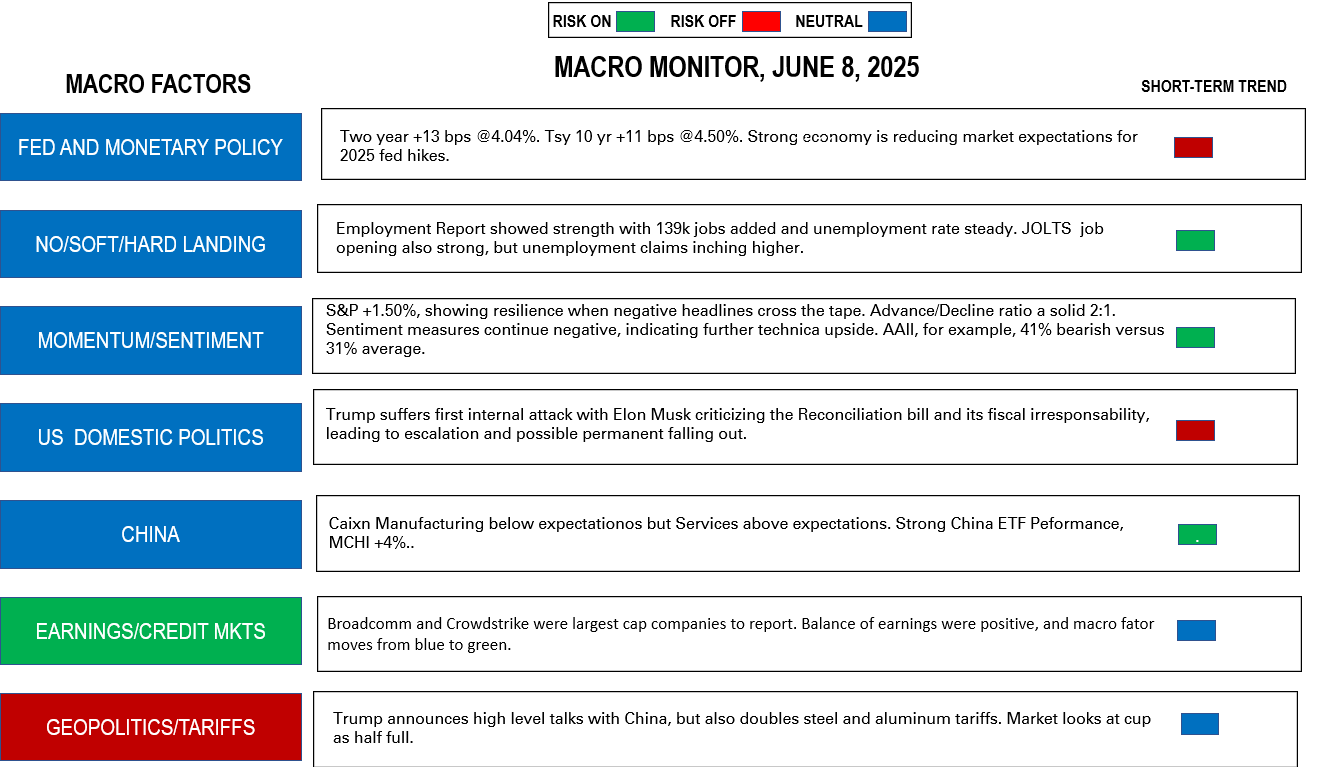

Here is this week’s Macro Monitor, flashing a slight “risk-on.”